Thousands of years ago people looked at the world and said, ‘hmm, this doesn’t make any sense’ and so they tried to understand what it all meant. They attributed the seasons to the whims of gods created in their own image- grumpy, distrustful, passionate, loving and, well, human, all too human. However, one question which caused much consternation was, how did life begin? How was the planet made? Why do the stars twinkle? Thusly, they created creation myths. Each culture has one, some more graphic than others, but mostly everything stems from one thing. Destruction, be it the petulant wills of the gods or something else.

A few thousand years later, some people were still trying to answer the same questions. They looked at the world and they asked, how was the planet made? What are the wanders in the sky (πλανήτης (planētēs), meaning ‘wanderer’)? and how did life come to be? Theories were formulated, more complex than before as mythology gave way to philosophy, which spawned rudimentary science, and the conclusion was reached, everything stemmed from a form of destruction, be it the petulant wills of the gods or something else.

In the modern world (21st Century for those of you who will read this in a hundred years time and laugh at my use of the world ‘modern’) we have answered the great questions. We know how things are ‘made’ with chemicals, physics etc. Theology and philosophy are mocked more than they are respected and incorporated into daily life. We are living in the scientific age. The industrial revolution was a thing of beauty, looked at as one may look at an elderly person, ‘cute’, without any understanding of the life of the person whom they look at. Mythology is no longer needed as we have science. Everything is answered and science alone brings us truth. Right? Um…no.

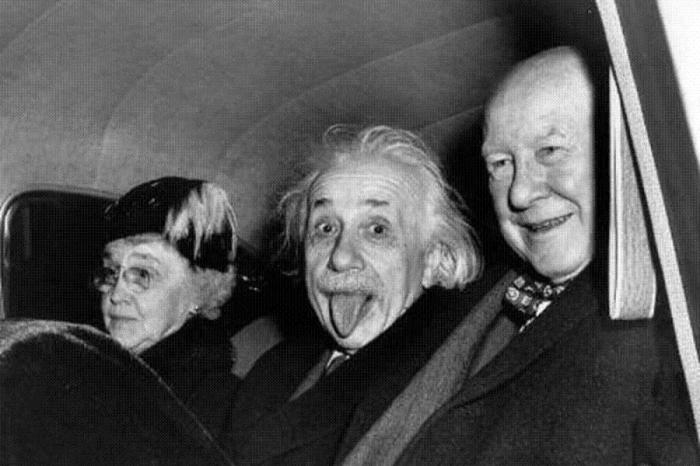

In an essay that Einstein wrote, which can be found in his book ‘Out Of My Later Years’, Einstein wrote ‘science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind’. Although we won’t go into it now in depth, Einstein essentially says in his essay that you cannot have one without the other and that each great theologian was also a great scientist and vice versa, referencing the likes of Spinoza and Newton. I would happily argue that all philosophy, science etc. is the search for a higher Truth, that is answers to the question ‘do we exist and, if so, why?’, and that all is theology- the attempt to create a framework in which one can study (a)’God’, however, let’s go back to the original story and how the ancients, thousands of years apart, had to create fairy tales to explain how everything was created. We no longer have the need for such things, living in the modern age, as we know, all too well, that once upon a time there was some stuff, no one knows what or where it came from, in some place, no one knows what or where it came from, and suddenly for some reason, no one knows what or where it came from (the reason) it all went BANG! and the stuff which had appeared from somewhere, or nowhere, was chucked out into something, or nothing, and then it cooled down and some monkeys went ‘hey, iPads, they seem cool’.

It is easy to dismiss those that came before as being silly children creating fireside stories to explain things beyond their comprehension and, possibly, ability to ever know, yet if we look closely at ourselves we will see, as there is not much real difference between the thought of the earliest humans and the Ancient Greeks, nor is there much difference in the thought of the earliest people and us.

Hmm…

‘till next time